Staying Connected

By Ben Okopnik

For most people, the meaning of "mobile Internet" ranges from an amusing toy to the Holy Grail of the future of computing. For me, however, it's no more or less than a basic necessity: I live aboard a boat that is anchored out, away from marinas and land-based connections - and when I travel for business, I'm either on the road, at a hotel (which may have one of a wild variety of connection methods - or none), or at a client's site (generally excellent connectivity, but via another wide variety of connection methods.) In some ways, all of the above makes an excellent laboratory for exploring the limits of Linux - in fact, of both computer hardware and software. In this article, I'm going to explore the systems that I have evolved for coping with this wide variety of options over the years; at this point, all my systems work well and smoothly enough that I am able to reliably do the work that is required of me by both my clients and my duties here at the Linux Gazette, and believe that my experience could serve others who find themselves dealing with similar challenges.

Just to note some recent behind-the-scenes changes at LG that eventually resulted in prompting me to write this: thanks to our own Rick Moen, all our mailing lists are now hosted on a unified, essentially spam-free system that also provides an important level of redundancy (e.g., if the LG web host goes down, the mailing lists are not affected - and we still have an avenue of communication other than POTS.) However, in the process of thinking about the attractions of using such a host - much of my own email, personal and LG-related, passes through linuxgazette.net - I got so involved in the excitement of "upgrading" that I lost track of the underlying basics of my mail system. A few days of following that track reminded me... and I very quickly switched back to the system that I'd been using all along. That's not to say that Rick's system can't be a viable part of my mail solution - in fact, I'm very glad to have it as an option and am grateful to Rick for providing it - but that the situation served as a very powerful reminder that there are larger issues to consider in switching over, and that those issues must be considered first, and that any changes must fit within those requirements.

On the gripping hand, as the crew of INS McArthur might say, all this theoretical stuff will have your head spinning if you take it too far. :) In short, it's not all that difficult. Let's take a good look at the hardware and software that make all my systems work together. For those of you who may be expert (or simply know more than I do) in any one of the subsystems I mention here, please feel free to tender any suggestions for simplifying it even further; they will always be welcomed with an open mind.

The Building Blocks

Hardware

- • Acer Aspire 2012 laptop (802.11 B/G wireless, Ethernet port)

- • Nextel cellular phone (Motorola i730) with packet service (PacketStream Gold) and a USB-to-phone cable

Software

- • pppd (the Point-to-Point Protocol Daemon)

- • Exim (SMTP server)

- • fetchmail (mail retrieval utility)

- • Mutt (mail reader)

- • Various browsers (primarily w3m) and other Net utilities

- • Various Net tools for troubleshooting (ping, route, nmap, netstat, host, etc.)

Doesn't seem like much, does it? And yet...

Obviously, your laptop does not have to be the same as mine; however, there are important features that are required to achieve the same functionality - the primary one of which these days is the wireless interface, closely followed by the hard-wired Ethernet port. Yes, the Acer does have a modem... but in the last few years, I have found no need for it.

For me, the key to the broad availability of connections almost anywhere I go is my Nextel phone. Several years ago, I switched to PacketStream Gold ($50/month for unlimited network connectivity), and have been highly satisfied with its rock-steady solidity; I used to have their $20/month CDPD service, which dropped my connections constantly.

WARNING: for those of you considering this route, be aware that it is very, very slow. Even for those of you who are used to nothing more than dial-up service, this is going to be about 1/3 to 1/4 the speed of your connections. Snails and turtles laugh at how slow this type of connection is. Ice Ages come and go in a rapid procession while you wait for a single character to come across the wire. The Universe progresses toward heat death in huge leaps during the retrieval of a single email. Deities and highly advanced alien creatures, usually immortal and unaware of time, become enlightened as to the nature of it - and how infinitely long it is - by watching the loading of a small, text-only web page through this connection.

Have I made my point yet? :)

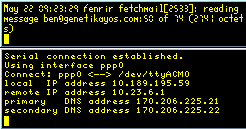

Connecting via cell phone

The actual average speed of connecting through Nextel, measured by me through many, many long downloads and over a variety of protocols, times of the day, and locations is pretty close to 10kb/S; that is, approximately 1 kilobyte of data transfer per second (contrasted against the 4 or even 4.5kB for the average modem.) A 1MB file takes about 16 minutes to retrieve; the average email takes 2-10 seconds. In reality, when the only other option is no connection at all, this is not all that bad - and can even be seen as absolutely wonderful. Here's what's required to make it work:

- Connect the phone to the laptop via the Nextel USB cable

- Load the cdc_acm kernel module (I use 'hotplug', so for me this happens automatically)

- Connecting by "dialing" via 'pppd'

That's pretty much it; no dialtone, no modem negotiation... it just works. However, making it do so originally required a good bit of research - so, for those of you who decide to go this route, the correct settings for 'pppd' are reproduced below.

----- /etc/ppp/peers/cell-hs ------------------------------------------- -detach noauth connect "/usr/sbin/chat -v -f /etc/chatscripts/cell-hs" local crtscts /dev/ttyACM0 57600 defaultroute replacedefaultroute noproxyarp usepeerdns ----- /etc/ppp/peers/cell-hs -------------------------------------------

----- /etc/chatscripts/cell-hs ----------------------------------------- '' ATZ OK ATQ0&K3 OK ATDTS=2 ----- /etc/chatscripts/cell-hs -----------------------------------------

A bit of explanation for the above: I want to see the connection being made, just in case it fails; therefore, rather than backgrounding 'pppd' and letting the diagnostic output go to a log file, I leave it in the foreground by setting '-detach'. Most of the following syntax is relatively standard for 'pppd' configuration, but there are a few key points:

replacedefaultroute - Since this mode of communication will be primary whenever it's enabled (local connections, e.g. NAT to other machines on the home network, will be in pass-through mode rather than a connection to the Net), the default route supplied by Nextel should be the primary one.

usepeerdns - Ditto for DNS; whatever is supplied by Nextel is the right thing to use when the cell connection is up.

The 'chatscripts' negotiation with the peer for this connection is quite simple: expect nothing, send 'ATZ'; expect 'OK', send 'ATQ0&K3' (enable result codes and selective data compression in the modem - the latter is, again, a requirement for this cellular protocol!); expect 'OK', send 'S=2' (this is where a 'normal' modem negotiation would have the phone number to be dialed.)

Once past the initial setup, this configuration has not needed any modification or adjustment in several years. I invoke it either by typing 'pppd call cell-hs' in a console and switching to another console to do my work, or - if I'm running X, which is usually the case - clicking on a toolbar icon that invokes a tiny xterm in the corner of my desktop by running

xterm -geometry 40x10-0-0 -name ppp -bg black -fg yellow -fn 6x9 -e pppd call cell-hs &

The actual script does just a little more than that - it invokes 'fetchmail' via another script that checks to see if it's already running, then calls yet another script which creates a named pipe to "catch" the filtered output from 'fetchmail' and send it to another tiny xterm which shows how many messages there are and which one is currently being downloaded. The reason for me having all this in three scripts instead of one is that they are individually useable for different things: "fet" is a shortcut for launching 'fetchmail' in daemon mode with my standard options, and "cm-small" provides me with a tiny window showing the email info - something I can use with the other types of network connections as well.

The main connection window (or the output of the 'pppd' invocation in the console) shows the status of the connection, and dies immediately if something goes wrong (i.e., the phone battery runs down, or the phone is unplugged.) It also allows me to kill the connection manually by selecting the window and hitting 'Ctrl-C'. That takes care of all my needs in regard to connecting in this manner.

Connecting via hard-wired Ethernet

For the most part, hotels and clients' sites usually have DHCP running, and connections are trivially easy:

ben@Fenrir:~$ su -c /sbin/pump Password:

However, I often encounter sites where there's no DHCP, and my network connection must be configured manually. In fact, given that I will usually be flipping back and forth between the work setup during the day and the hotel setup in the evening, it makes sense to have a script that "remembers" a set of the necessary values; I call mine 'eth'. When invoked as root, it allows you to specify the IP, the netmask, a pair of DNS resolvers, and the gateway address - and uses the default (last used) address if you enter nothing at a given prompt. This way, once it's given a set of values on Monday, setting up in the morning for the rest of the week consists of simply calling the script and hitting 'Enter' several times.

Hint: since the local sysadmins can sometimes be hard to find, or are unwilling to be disturbed (Beware of disturbing a Sysadmin in his deliberations, young Jedi; never forget that you are susceptible to great blasts of fire, and will taste good toasted with just a dash of hot sauce...), the wise guest on a network will use 'tcpdump -i eth0' to get an idea of the range of local IPs, perhaps take a look at the "/etc/hosts" on a local machine, and run 'nmap -sP' to discover the hosts that are up within that range before choosing his own IP. Picking one that conflicts with an existing machine on the network could have highly painful repercussions!

Again, there's not much more to setting up hard-wired Ethernet connections than this, at least for me. That's not to say that I haven't run into network problems, but they weren't specific to the type of connection - just usual network-related problems. Here are a few examples just in case you run up against some:

When you've got no network response at all

- • Check the physical connection. Do you have a 'connect' light? How about the 'activity' light?

- • Ping the gateway, or one of the machines on the same segment as yours. Are you really using the right IP and netmask, or did you fumble-finger the numbers? "Destination host/net unreachable" messages are a pretty good indication of the latter.

You can reach the local machines, but can't get out

- • Ping an external, Internet-reachable machine by its IP (it's a good

idea to have a few reliable IPs saved somewhere just for this situation.) If you

can reach them by IP but not by name, check the DNS resolvers in

/etc/resolv.confby using the 'host' command (i.e., 'host <known_valid_host_name> <resolver_IP>'). - • Use 'route' or 'netstat -rn' to see what you've got set up for a gateway. Does it correspond to the actual gateway IP? Can you ping it? Does 'route' just "sit" for a while before giving you an answer? This often means that it can't resolve your gateway - definitely cause to question the validity of your nameservers.

Also, just in case, keep an alternate list of DNS servers (I store mine in

/etc/resolv.conf.alt); DNS seems to be The Problem Child of

many systems. Loop over the list to find reachable/working DNS hosts like

this:

for n in $(awk '/^nameserver/{print $2}' /etc/resolv.*)

do

echo "Using $n:"

host -Q -s 1 netscape.com $n

done

This will show a rather obvious listing of responding servers as well as ones that are unreachable. If the local DNS server isn't working, and you can see a couple that are, don't bother swimming against the current - use what works.

Connecting via wireless Ethernet

Much like the hard Ethernet interface, most wireless configuration these days happens via DHCP:

ben@Fenrir:~$ su -c '/sbin/pump -i wlan0' Password:

However, as time goes on and I keep running into more and more radically different configurations - mostly the auth keys necessary for different locations where I connect - I find myself becoming more and more fond of '/sbin/ifup'. Using this method, you can specify a stanza within your '/etc/network/interfaces' file with the following syntax:

/sbin/ifup wlan0=cafe

where 'cafe' is a stanza in the 'interfaces' file which sets all the necessary options for connecting at your favorite cafe, e.g.

iface cafe inet dhcp

# Set mode to 802.11B/G

pre-up iwpriv wlan0 set_mode 6

pre-up iwconfig wlan0 essid "mi_casa"

pre-up iwconfig wlan0 key 12345ABCDE

wireless_mode Managed

For more info, see 'man interfaces'.

Troubleshooting wireless configuration - well, the bits listed in the Ethernet section above are almost all applicable (the only difficult part is checking the "plug".) The main tool I use for checking the availability, type, and authentication requirements of the local WiFi networks is "iwlist wlan0 scan"; go thou and do likewise. Unfortunately, the man pages for the iw* utilities are a bit cryptic, and the syntax can be very odd - but the above directions, plus the use of 'iwconfig' (and occasionally 'iwpriv') to set up the specifics of the interface for a given network usually seems to be all that's necessary.

The Mail System

Now that we have managed to actually connect to the world, there are several considerations - particularly on the slow end of the connection spectrum - that we need to take into account. Browsing the Net is rather simple by its nature: we expect to click 'Reload' once in a while, and if the page fails to load, it's not considered a big deal. With mail, however, all of this becomes critical. The key principle of configuring this system should be much like the basis of TCP/IP: at every stage, you must get either delivery or notification of failure. No exceptions.

There must be thousands of ways to set up even a simple mail system. I suspect that by this point I've done most of them - and in most cases, abandoned the setup and moved on because it did not provide the reliability that I needed with my configuration. In the end, I've settled on the setup that I've mentioned above - Exim as the MTA, Mutt as the MUA, and 'fetchmail' for retrieval. Here, I'll discuss the specifics of the configuration and the various options that I use when working in odd situations.

The configuration files that make all of this work are

- • ~/.fetchmailrc

- • /exim/exim.conf # A symbolic link to one of the following

- • /exim/exim.conf.ssh

- • /exim/exim.conf.normal

I use a script, 'eximconf', to switch the symlink between 'normal' and 'ssh' operating modes for Exim. 'fetchmail', on the other hand, requires no adjustment - the non-working stanza simply fails (and produces a report of that failure in the '/var/log/mail*' and '/var/log/messages' files.)

Running the system in "normal" mode

Outgoing mail

MUAs (Mutt, 'mail', Lynx's mail interface, etc.) perform their default operation - i.e., connect to port 25 on the local host, and pass the mail to the MTA (Exim). Exim, in turn, does what it's normally supposed to do: it connects to the mailhost for the domain to which I'm sending the email, passes the mail to it, and goes back to sleep. All is well - and in case of any failures, the message will remain in my mail queue and Exim will notify me about it. Most importantly, I've configured Exim to "auto-thaw" any "frozen" messages on the queue:

freeze_tell_mailmaster = true auto_thaw = 5m

This has mitigated 99%+ of the queue problems that I used to have to handle manually; it seems that a few retries are all that it usually takes.

Incoming mail

Fetchmail, which is invoked automatically as soon as I dial up (or manually, by running the 'fet' script whenever I feel the need), executes the highlighted stanza in my ~/.fetchmailrc (the password, etc. have been changed to protect the not-so-innocent):

# Grab the mail from the server poll "mailserver.com", user "me", password "shh_its_a_secret"; # Grab it from the mailserver via SSH tunnel poll "localhost", port 2110, user "me", pass "shh_its_a_secret";

The second stanza (via SSH) fails for now, since there's no "listener" on

localhost:2110 - but will come in useful later.

A question you might be asking by this point is - why do I need to run an MTA at all? Why don't I just spin my mail off to an off-machine MTA (a.k.a. a "smarthost" at the ISP) and let it handle all those problems? Or, looked at another way, why don't I just use Mozilla's mail client and forget about all that complicated stuff?

There are a number of important reasons:

- • Linux is a "networked OS". That is, it assumes a Net connection and a fully-operational mail system as a prerequisite for complete functionality (think "reportbug", "apt-get", etc.) Mozilla's mail client (which, by the way, implements a stub MTA of its own) will not work with, say, "reportbug", will not allow you to send mail by selecting a "mailto:" link in Lynx, etc. - in other words, you will lose a major part of what makes Linux operate as a unified whole.

- • In order to do any off-line mail (other than saving your composed emails as drafts and sending them the next time you're connected), you need some sort of a spooling mechanism - and an MTA provides one. Once it's in place, your actions in sending an email remain exactly the same whether you're on-line or off: simply compose and send. The MTA will rotate them off automatically the next time you're connected.

- • Error reporting. This is the big one for me - and it should be for you, if getting your email to its final destination is important to you. Your MTA is your agent for negotiating the email hand-off; if anything at all goes wrong, you - and not some ISP's mail administrator - will get the report. If the mail that you're sending concerns an important and time-sensitive business obligation, you'll want to know for sure that it has been delivered; if it fails, and you see the failure, you'll at least have the option of getting your information there by a different route.

- • Connecting without an ISP. What happens if your Net access is all through Net cafes and publicly-available networks? After a while, you start to wonder exactly why you're paying money to that ISP of yours. An email address? There's Gmail and Yahoo and Hotmail and Netscape and a trillion (give or take a few) others who will be more than happy to give you a free, non-ISP-connected email account just for the privilege of having your data (you're a tasty little chunk of mineral-rich ore in the data-mining business to them - and they can now ask you to reveal any kind of personal information. Most people, now that they feel they've "established a relationship" - not you, surely, you're way too smart for them! - will reveal it without a second thought. No, they're not giving it to you out of the goodness of their hearts.) Anyway, the only reason that remains after all the external hoo-hah and noise and flash has been stripped away is an MTA - a way to get your mail out to the world. Running your own fills that need.

There are a number of other reasons - it's a topic I could discuss for hours - but suffice it to say that I've tried a number of variations for my mail system over the years, with and without an MTA. To quote Pearl Bailey, "I've been rich and I've been poor. Rich is better."

So, the above configuration is fairly simple and generally sufficient - but there are times when it won't work. Those of you who have tried configuring an MTA while connected through some of the popular ISPs (Earthlink, AT&T, etc.) already know what I'm talking about: a number of them block port 25 so that you can't do your own SMTP! In addition, many of them also block the various POP ports so you can't do your own mail retrieval. According to them, you must use their "smarthosts" (i.e., SMTP and POP servers) - or stick with web-based mail. I find these restrictions - both taken together or either one all by itself - unacceptable, untenable, and outrageous.

Mind you, this is not some arbitrary stance on my part. I find it absolutely unacceptable that an SMTP "smarthost" can hold my mail for two weeks without notifying me (something that lost me a $30,000 contract on one of the many occasions when it happened.) I find it untenable to be restricted to Web-based mail, where the mail I send is not integrated into my mail archive, which provides a contiguous legal record (among other uses, ones that are just as important) of the work that I'm doing for my clients. On top of all that, I find it outrageous for an ISP, due to their own incompetence in securing their mail system, to deny me full Net access for which I have paid - only to find that they have lied about it later, after they have my money.

Note that I do not pay any of the usual dial-up ISPs any longer, and do not plan to do so ever again. :) Fool me once, shame on me, fool me twice... I don't think so.

So, what do I do when I'm stuck behind a firewall that blocks those ports (some of my clients use those ISPs, who continue these practices on their DSL, cable, etc. connections)? I jump around them via SSH port forwarding, a system so capably described by Mike Chirico in his article in this issue. However, my configuration differs slightly from the one he suggests, since I use it in several different ways and need just a bit more modularity and flexibility.

Running the system in "SSH" mode

Outgoing mail

There are two things that I need to do in order to configure my mail for port forwarding: tell Exim to use the correct conffile, and forward the local port to the remote host/port that I need. Both of these are easy: the first is done by a script which toggles the symlink, "/etc/exim/exim.conf", to point to "/etc/exim/exim.conf.ssh" (instead of the usual "/etc/exim/exim.conf.normal"). The second happens automatically whenever I create an SSH connection to my mailhost; I have configured my ~/.ssh/config file to take care of it.

Host mail Hostname mailhost.net LocalForward 2025 mailhost.net:25 LocalForward 2110 mailhost.net:110 KeepAlive yes

This matches an entry in "exim.conf.ssh":

# This transport is used for delivering messages over SMTP connections. remote_smtp: driver = smtp smtp2025: driver = smtp service = 2025 end

The result of the above two actions, as well as all of the configuration, is to create a tunnel from port 25 at mailhost.net to port 2025 on the localhost (as well as one from mailhost.net:110 to localhost:2110. Why is this last bit important? See "Incoming mail", just below.) Exim then pushes its mail to localhost:2025, which then "magically" appears on mailhost.net:25 - without ever using port 25 at the ISP's servers. Clever, eh?

Incoming mail

By now, this is probably pretty obvious to anyone who's been following along. Now that port 2110 does have a listener on it - which is actually port 110 at mailhost.net - the second 'fetchmail' stanza kicks in while the first one fails due to the blocked POP port:

# Grab the mail from the server poll "mailserver.com", user "me", password "shh_its_a_secret"; # Grab it from the mailserver via SSH tunnel poll "localhost", port 2110, user "me", pass "shh_its_a_secret";

So, what I have as a result of the above configuration are two mutually-exclusive retrieval stanzas - exactly what I want. The only mild oddity resulting from this is a warning message in the logs:

fetchmail[4330]: Server CommonName mismatch: mailhost.net != localhost

I know what it's saying, but I haven't found any way to tell it "yes, I know, and it's OK." It doesn't create any problems, and I don't mind it at all.

Web Surfing

Over time, my choice of favorite browsers has focused down to three (or four, since I use Mozilla and Firefox more or less interchangeably): 'w3m' is my primary "interface to the world", 'lynx' is used for various specialized Web tasks (scripted HTTP downloads, receiving the output of piped HTML, one-column formatting and text output for plain-text conversion, traversal of a web page to check that all the links are alive, etc.), and Mozilla or Firefox for the graphical environment whenever I need such a thing. The nicest part of doing it this way is that you can "pass" a web page from 'w3m' to any other browser: simply define them as "alternate browsers" in 'w3m's configuration, and call them with "shift-m" ("2-shift-m" for the second one, "3-shift-m" for the third one, etc.) This allows me to "zoom in" on the page that I need with a text mode browser - e.g., when I'm searching for info on the Web - and fire up the graphical browser when I find exactly what I need.

One of my favorite scripts, one that I use many times a day, is my own 'google'. This drops me into Google's "Advanced search" page when invoked by itself - or can take a Google-formatted query as an argument:

ben@Fenrir:~$ google "how dare you not be me" artist -kinkade

The above query will match those web pages in which the double-quoted string exists as a phrase. These pages must also contain the word "artist" and must not contain the word "kinkade" (I was looking for the works of Barbara Kruger, even though I couldn't remember her name, but wanted to eliminate the links for the "Kinkade Crusade", a different artist altogether.) This script pulls up the search pages for my perusal - and if I decide that I need to see the graphical images, "2-shift-m" gets me an instance of Firefox pointed to the current page. Even on a very slow connection, this method gives me everything I need from the Web quite quickly.

Conclusion

Despite the great amounts of verbiage expended above, the result of all that configuration is a very simple and flexible setup that can be made to work with just a couple of commands and in just a couple of seconds literally anywhere that a connection is available - and for those places where it's not, I have my slow-but-reliable cell phone. Lately, I've been looking at a high-speed cellular network card from Verizon - I've spoken to several current users who report 5Mb/S rates all along the East coast of the US. However, paying the initial fee for the card and the premium for the service and paying two different cellular companies for the privilege of using the airwaves seems like a bit of overkill for the moment. It may become worth the money and the trouble sometime soon, but for now, I'm quite satisfied. Speed increases and seamless operation are sure to be in the future... but for this Linuxer, staying connected is not a challenge any longer.

Ben was born in Moscow, Russia in 1962. He became interested in electricity

at the tender age of six, promptly demonstrated it by sticking a fork into

a socket and starting a fire, and has been falling down technological

mineshafts ever since. He has been working with computers since the Elder

Days, when they had to be built by soldering parts onto printed circuit

boards and programs had to fit into 4k of memory. He would gladly pay good

money to any psychologist who can cure him of the recurrent nightmares.

His subsequent experiences include creating software in nearly a dozen

languages, network and database maintenance during the approach of a

hurricane, and writing articles for publications ranging from sailing

magazines to technological journals. After a seven-year Atlantic/Caribbean

cruise under sail and passages up and down the East coast of the US, he is

currently anchored in St. Augustine, Florida. He works as a technical

instructor for Sun Microsystems and a private Open Source consultant/Web

developer. His current set of hobbies includes flying, yoga, martial arts,

motorcycles, writing, and Roman history; his Palm Pilot is crammed full of

alarms, many of which contain exclamation points.

He has been working with Linux since 1997, and credits it with his complete

loss of interest in waging nuclear warfare on parts of the Pacific Northwest.

Ben is the Editor-in-Chief for Linux Gazette and a member of The Answer Gang.

Ben is the Editor-in-Chief for Linux Gazette and a member of The Answer Gang.