Using Linux to Teach Kids How to Program, 10 Years Later (Part II)

In last month's article, I talked about the Logo programming language as a tool to help you introduce mathematics and programming concepts to kids. This month, I am going to take you one step further into Logo programming and show you some more advanced concepts like loops, conditional statements, procedure definition, and (do I dare?) even the concept of recursion.

Before we begin, though, I would like to make a small disclaimer: I've always thought of Logo as a programming language for kids only, and even though I've been writing these articles about using Logo to teach kids how to program, I know of quite a few universities that use Logo even in their graduate courses, to teach complex techniques in recursion and other programming topics. Therefore, don't think for a moment that Logo is just a toy: it's definitely fun and educational.

With that said, let's go ahead and learn some more Logo.

In Logo, we have the ability to teach our "programmable" turtle new words. To do that, we use the to keyword. It's with to that we define our procedures in Logo, and also have the ability to save our work to disk, which I will discuss later on.

Logo's Hello World

If you decide to do more research and learn more about Logo on your own, you will probably see the following procedure as one of the very first Logo examples:

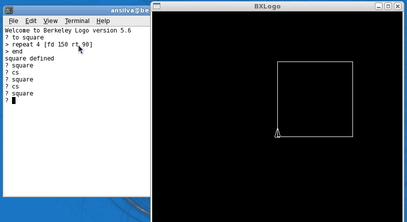

to square repeat 4 [fd 100 rt 90] end

That's how we teach Logo's turtle the word "square". To square means: Repeat the following 4 times: go forward 100 pixels and turn right 90 degrees. Now, when you call square in the Logo interpreter, the turtle will draw you the square you are asking for. The only problem here is that, if you exit your interpreter with the command bye, the turtle will forget that word, and eventually teaching the same word over and over again will get pretty boring, even for a kid.

The solution is to save your new procedure (a.k.a. word) into a file, and load that when you start the interpreter. To save your work use:

? save "square.logo

where, like the help command we talked about last month, the file name must be preceded with a double quotation mark. Once you save your new defined word, you will see a text file called square.logo in the same directory where you started your interpreter.

As you start to familiarize yourself with Logo, you will always have the choice to write your code directly to a text file, and then load it via the interpreter. To do that:

? load "square.logo

Let's say, once you teach the turtle the word square, you want to change the definition of it a little. Maybe you want to add colors or make the square bigger. Well, Logo will not let you create a new square word, and it will complain with the following message if you try it:

? to square square is already defined

If you want to modify an existing word you taught the turtle, you need to use the ed command.

? ed "square

Note: For ed to work, you must have the shell environment $EDITOR set to your favorite text editor. I usually run: export EDITOR="vi" in my shell before starting my Logo interpreter.

With all that said, I'd like to give you one final and more complex, yet fun, Logo example. The example below is recorded as if we were typing it directly into the Logo interpreter, and then saved to a file called example.logo.

Welcome to Berkeley Logo version 5.6 ? to pick_color > output pick [1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15] > end pick_color defined ? to colorful_circle :size > if :size = 1 [stop] > setpencolor pick_color > arc 360 :size > colorful_circle :size - 1 > end colorful_circle defined ? save "example.logo

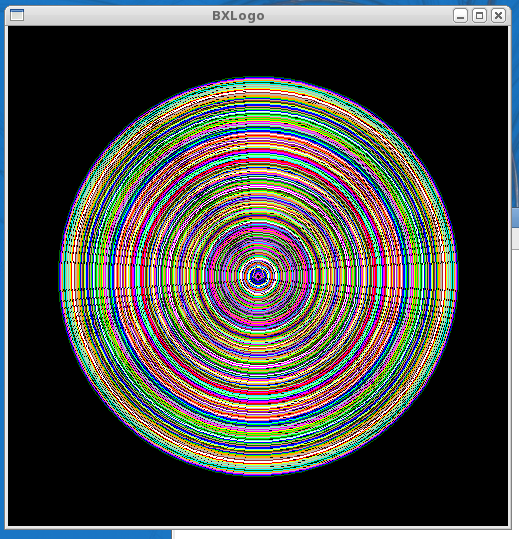

In the example above, I teach Logo's turtle two new words: pick_color and colorful_circle.

The word pick_color is basically a function that uses the command pick to randomly choose a number between 1 and 15. The command output is used to return the value picked by pick.

The word colorful_circle is quite a bit more complex, and it packs a lot of new Logo features. If you look at the very first line where colorful_circle is defined with to, we have :size as a parameter for it. In Logo, variables are identified with a colon (:) in front of their labels.

Then, we have an if statement, checking if :size equals 1, and, if so, to leave the procedure. This if statement is known as a base case, because colorful_circle is a recursive word, which means it calls itself to execute a rule, and it will stop doing so only when the base case is met.

With setpencolor pick_color, the turtle will be able to choose whatever color it wants to draw the next circle it is going to draw. (Note: setpencolor was discussed in last month's article).

After a color is picked, and set, it's time to draw a circle with the arc command. To understand the arc command, let's use Logo's help. In the interpreter, type:

? help "arc ARC angle radius draws an arc of a circle, with the turtle at the center, with the specified radius, starting at the turtle's heading and extending clockwise through the specified angle. The turtle does not move.

So, the arc command takes two parameters: an angle and a radius. Because we want to draw a circle, it makes sense that my arc angle be 360 degrees. The radius, it turns out, will be whatever the variable :size is. If :size changes, we will have different sized circles being drawn by the turtle.

Finally, we call colorful_circle. Yes, you are seeing it right: it is the very same word we are teaching the turtle, but we are subtracting 1 from the original :size for the word. This completes our recursion. We use recursion in this example to decrease the :size of the circle the turtle draws, and, when the :size becomes 1, the turtle stops drawing.

Executing example.logo:

Welcome to Berkeley Logo version 5.6 ? load "example.logo ? colorful_circle 200

The above will give you the following output:

Conclusion:

Are you confused yet? Probably not, but that doesn't mean the kids will get it all at first, so don't get frustrated with them. They don't need to be able to know recursion to discover Logo. I've said it before, and I will say it again: enjoy your time with them, teach them the basics, let them watch you code, let them pick colors, let them choose shapes on their own, and hopefully someday they will realize that programming and logical reasoning can be as much fun as things like playing games or reading a book.

Talkback: Discuss this article with The Answer Gang

![[BIO]](../gx/authors/silva.jpg)

Anderson Silva works as an IT Release Engineer at Red Hat, Inc. He holds a BS in Computer Science from Liberty University, a MS in Information Systems from the University of Maine. He is a Red Hat Certified Engineer working towards becoming a Red Hat Certified Architect and has authored several Linux based articles for publications like: Linux Gazette, Revista do Linux, and Red Hat Magazine. Anderson has been married to his High School sweetheart, Joanna (who helps him edit his articles before submission), for 11 years, and has 3 kids. When he is not working or writing, he enjoys photography, spending time with his family, road cycling, watching Formula 1 and Indycar races, and taking his boys karting,